UPDATED: November 2019

With a cabinet announcement looming, what will it mean for British Columbia?

.jpg)

Sir John A parachuted into Victoria in 1878

B.C.’s place at the Cabinet table was at the head of the table in the 1870s when Sir John A. MacDonald was elected from Victoria in 1878, despite never having seen the place. He would eventually visit Victoria once he fulfilled the ultimate the election promise – the construction of the CPR.

Who have been B.C.’s heavyweights at the cabinet table? An historical review reveals British Columbia’s conflicted past in dealing with race relations and uneven influence compared to its provincial peers.

The early years ~ B.C. notables in Cabinet

In the late 1800’s, Edgar Dewdney was elected from Yale B.C. and served as an MP under Sir John A. MacDonald, becoming a partisan loyalist, personal friend, and ultimately an executor of his will. Lured to B.C. by the Gold Rush, Dewdney’s name is remembered through major roads (Dewdney Trunk) and localities, principally for his role in surveying the province. John A. dispatched him to oversee the territories as a direct report where he dealt with the Riel Rebellion and the demise of buffalo herds and resulting starvation. Not averse to mixing public duties with private land speculation, he eventually made it to federal cabinet in 1888 but not from B.C.; later, he was appointed B.C. Lieutenant-Governor. A B.C. cabinet minister? Not exactly, but an influential British Columbian at and near the cabinet table, yes.

Hewitt Bostock founded The Province newspaper and went on to win as a Liberal MP from the riding of Yale-Cariboo in 1896 on the Wilfred Laurier ticket, serving one term. Reflecting popular opinion at the time, Bostock opposed further Chinese immigration, and he also called Italians “a menace”. Laurier would appoint him to the Senate where he would eventually serve as Leader of the Opposition in that body. Like many Liberals in English Canada, he supported Borden’s Unionist government over the conscription issue, but would return to the Liberals and sit in William Lyon MacKenzie King’s government as Minister of Public Works briefly, before becoming Speaker of the Senate. Not many federal politicians have a mountain named after them, but he does, near the Fraser Canyon.

Conservative Martin Burrell, representing Yale-Cariboo, served in Prime Minister Robert Borden’s Conservative and Unionist cabinets as Agriculture minister, Mines Minister, and Minister of Customs & Inland Revenue. He also served briefly in Arthur Meighen’s ministry. An interesting note about Burrell (a former mayor of Grand Forks), was that he was appointed Parliamentary Librarian in 1920 and served in this post until his death in 1938.

Future B.C. premier Simon Fraser Tolmie would serve in both of Arthur Meighen’s

Simon Fraser Tolmie

cabinets as Minister of Agriculture. In both stints, Meighen’s governments didn’t last long, out-wrangled by William Lyon MacKenzie King. Tolmie was recruited to return to B.C to take on the leadership of the B.C. Conservative Party, leading them to victory in 1928. Shortly thereafter, his government was caught in the jaws of the Great Depression and was dispatched by the voters in 1933 after one term. Along with Ujjal Dosanjh, Tolmie has been one of two B.C. premiers to serve in a federal cabinet. Other premiers, such as Amor de Cosmos, Fighting Joe Martin, and Dave Barrett, also served in Parliament.

H.H. Stevens aboard the Komagatu Maru

Conservative heavyweight H.H. Stevens served in Meighen’s brief cabinet (1926) then, later, for four years under Prime Minister R.B. Bennett.

He was a powerful Trade minister who crusaded against price-fixing. He resigned in epic fashion and created the Reconstruction Party which split the vote and destroyed the Bennett government in 1935. Stevens survived in his own seat in Vancouver Centre, but did not elect any other MPs.

He returned to the Conservatives thereafter but his political career fizzled out.

Stevens trajectory resembles both Maxime Bernier (started his own party in protest of leadership) and Jody Wilson-Raybould (Vancouver cabinet minister rebelling against prime minister). Like Wilson-Raybould, he won his own seat back in the subsequent election. Like Bernier, his party failed to launch, though his results were better, taking 8.7% of the popular vote in Canada, including 11% in Ontario (but no seats).

While he was unquestionably a force of politics in B.C. during the 1920s and 1930s, Stevens is also remembered for his role in stifling the Komagatu Maru and for reflecting public opinion during his time concerning Asian immigration: “We cannot hope to preserve the national type if we allow Asiatics to enter Canada in any numbers.”

Fishing boats seized during internment of Japanese-Canadians

Fear over Asian immigration was a multi-partisan issue, with labour leaders and Liberal politicians eager participants as well. Liberal Ian MacKenzie was sworn into Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s cabinet prior to the 1930 election. He won his seat but the government lost power. In 1935 he re-emerged as Minister of National Defence. He also became the first Government House Leader in the House of Commons. As B.C.’s top cabinet minister, he championed the internment of Japanese-Canadians during WWII, stating in the 1942 election: “Let our slogan be for British Columbia: ‘No Japs from the Rockies to the seas.”

H.H. Stevens is probably the most notable figure in Canadian politics coming from B.C. between Confederation to the end of WWII. But perhaps it was the librarian Martin Burrell who left the most lasting mark.

Moving toward modern times

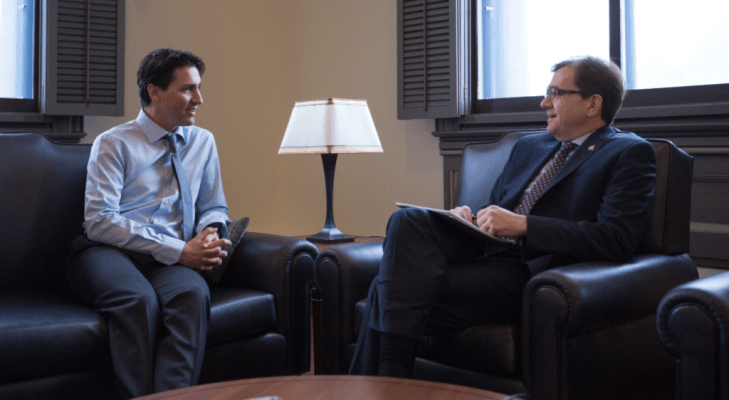

James Sinclair: Justin Trudeau’s grandfather

Coast-Capilano Liberal MP James Sinclair, the grandfather of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, served in Parliament from 1940 to 1958; he served as Minister of Fisheries from 1952-57. The Sinclair Centre, at the corner of Hastings and Granville in Vancouver, bears his name. Again, reflecting mainstream opinion, Sinclair’s comments on race bear mentioning. In 1947, post WWII, he spoke in favour of welcoming citizenship rights to the Chinese already in Canada, contrasting to the Japanese-Canadian population: “We have never had the feeling against the Chinese in B.C. that we have had against the Japanese”. He said he would support restoring voting rights for Japanese if the post-war dispersal policy proved successful. It wasn’t until 1949 restrictions were lifted.

Vancouver-Centre Liberal MP Ralph Campney served as Solicitor-General, Associate Minister of Defence and Minister of Defence under Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent. A WWI veteran, and lawyer, he served as political secretary to MacKenzie-King and was part of the Canadian delegation to the League of Nations in 1924.

Campney would lose in 1957 to Douglas Jung, the first Chinese-Canadian Member of Parliament; Sinclair lost in 1958, thus making way for new Liberal cabinet leaders from B.C. in the 1960s.

After 22 years in the wilderness, the Progressive Conservatives finally returned to power in 1957. The Diefenbaker era ushered in B.C.’s first dose of serious cabinet clout. From 1957-63, three senior ministers hailed from the west coast.

Two-time P.C. leadership contender E. Davie Fulton

Kamloops MP E. Davie Fulton, a leadership rival to Diefenbaker, was an influential Minister of Justice for much of that time; Vancouver Quadra MP Howard Green ultimately served as Secretary of State for External Affairs; and George Pearkes, Victoria Cross recipient, served as Minister of National Defence prior to his appointment as B.C.’s Lieutenant-Governor in 1960.

Fulton had sought the leadership of the Progressive Conservatives twice, finishing third to Diefenbaker in 1956, at age 40, and third again in 1967. Bilingual, he was the first true contender from B.C. for either of the major federal parties. In cabinet, he was a key player in the Canadian Bill of Rights, the Fulton-Favreau Formula (an earnest attempt to repatriate the Constitution), and Columbia River Treaty. Fulton left federal politics in 1963 to lead the B.C. Conservative Party, but was thwarted completely by W.A.C. Bennett and the governing Socreds, returning to federal politics one more time in 1965. After leaving office, he was elevated to the bench.

While Fulton was a contender, Pearkes was a hero. He was recipient of the Victoria Cross for conspicuous bravery in battle in World War I during the Battle of Passchendaele – his biography, released in 1977, is titled For Most Conspicuous Bravery. His name was revered in my father’s household as my grandfather, in charge of the militia in Drumheller, reported to Pearkes when he commanded the 13th Military District based in Calgary at the outbreak of WWII. He served in various capacities in Europe and in preparing for war on the Pacific, before retiring from the military in 1945 to jump in to politics, winning a seat for the PCs in Nanaimo. He was approached to be the leader of the BC Conservative Party but stayed with federal politics. When the time came for the PC’s to govern, he was a front bencher, and under his command in Defence, he recommended the cancellation of the Avro Arrow. He defended the decision during interviews for his biography, noting that he had been under huge pressure to stay the course. In 1960, he was appointed Lieutenant-Governor and had his term extended by Liberal Prime Minister Lester Pearson to serve through the centennial to 1968. Like Hewitt Bostock, he also has a mountain named after him, near Princess Louisa Inlet, among many other tributes and honours in his illustrious career.

The election of the Pearson government in 1963 continued B.C.’s cabinet presence with capable ministers, albeit at a less prestigious level than the Diefenbaker years.

Arthur Laing served in Pearson’s cabinet as Minister of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources then later as Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs. A former leader of the B.C. Liberal Party, Laing was the “B.C. Minister”; the bridge from YVR to the City is named in his honour. Laing’s wingman in cabinet was John Nicholson who served in various posts under Pearson.

B.C.’s decline in clout

While B.C. held at least three seats in cabinet during the first PET ministry (1968-79), B.C. seemed to lose ground with other provinces who had powerful ministers. B.C. was not without credible ministers, but it was the Marc Lalondes, Jean Marchands, Jean Chrétiens, John Turners, and Allan MacEachens that defined the Trudeau era at the cabinet level.

In 1968, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau brought young Vancouver MP Ron Basford into cabinet as Minister of Consumer and Corporate Affairs. He is remembered as the minister who championed Granville Island among other B.C. legacies. Laing continued in Public Works until 1972. Jack Davis served in Fisheries and Environment portfolios between 1968-1974 (before his election as a Social Credit MLA).

Len Marchand and Iona Campagnolo both served as Ministers of State in the mid 1970s, with Marchand finishing as Minister of Environment in 1979. Marchand was the first First Nation cabinet minister and first First Nations Member of Parliament in Canadian history. Iona Campagnolo was the first female federal cabinet minister from British Columbia. Had the Liberal government not met the buzz saw in 1979, it would have been interesting to see what would have become of Campagnolo and Marchand’s budding cabinet careers. Marchand went on to serve with distinction in the Senate, being an important voice for indigenous issues. Campagnolo went on to serve in many important public duties, as president of the Liberal Party of Canada, and as Lieutenant-Governor, one of three formal federal cabinet ministers to do so, along with Pearkes and John Nicholson.

Senator Ray Perrault, a former leader of the B.C. Liberal Party who went to defeat Tommy Douglas in 1968 and serve one term in the House of Commons, served as Government Leader in the Senate from 1974 to 1979. Perrault was the heart and soul of the party among grassroots Liberals for decades.

The short-lived Joe Clark government featured prominent B.C. politicians like Minister of Environment John Fraser, Defence Minister Allan MacKinnon from Victoria, and Minister of State Ron Huntington (father of former Delta South MLA Vicky Huntington). Fraser had run for leader in 1976, dropping off on the second ballot but delivering his support for Clark. Their tenures were short-lived when the Clark government was defeated in the House on December 13, 1979 and disposed of at the ballot box in February 1980.

When PET was campaigning again for election in 1980, he had the makings of a strong front bench from B.C.. Popular ex-mayor of Vancouver Art Phillips had been elected to the Liberals in 1979, serving in Opposition. Former B.C. Liberal leader Gordon Gibson contested North Vancouver-Burnaby while renowned resource economist Peter Pearse sought election in Vancouver Quadra. That would have been a strong trio of B.C. ministers, however, none were elected, nor were any other Liberals in B.C., Alberta, or Saskatchewan. It was a western wipe-out, much worse than Liberal setbacks in 2019. Senators Jack Austin and Ray Perrault became B.C.’s unelected representatives in Cabinet. Perrault was later dropped, contributing to B.C.’s alienation from the Liberal Party.

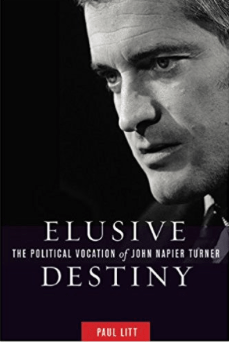

When Prime Minister John Turner decided to seek office from Vancouver Quadra in 1984, he sought to bridge the divide between the Liberal Party and the west coast. While he gained his seat (in the face of an electoral onslaught), he alone was elected from B.C.

Turner’s B.C. story is a compelling one. He spent his early years in Rossland and, while his formative years were spent in Ottawa, he returned to UBC for university (his stepfather was Lieutenant-Governor) where he was very much Big Man on Campus along with being Canadian 100 metre sprint champion. His B.C. years are chronicled in Elusive Destiny, an apt title for a political giant who’s timing was off. (Incredibly, his Olympic dreams were dashed when his car was hit by a train on the Arbutus Corridor). Turner served as MP for Vancouver Quadra for 9 years, retaining his seat after relinquishing his leadership to Jean Chretien. He had a strong B.C. connection but Turner was really a pan-Canadian instead of being owned by any region, representing three provinces during his illustrious parliamentary career.

The Mulroney-Chretien eras

From 1984 to 2004, B.C. had a steady presence at the cabinet table, not strikingly influential, but it produced our first and only B.C.-raised prime minister.

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney came to power in 1984 riding a wave of western alienation, but he also won big in Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes too.  It was a huge mandate. “Red Tories” John Fraser and Pat Carney, an upset winner over Art Phillips in 1980, led the B.C. contingent in cabinet. Fraser went to Fisheries and Carney to Energy – two significant portfolios. Carney was the first woman from B.C. to lead a department (Campagnolo was a Minister of State).

It was a huge mandate. “Red Tories” John Fraser and Pat Carney, an upset winner over Art Phillips in 1980, led the B.C. contingent in cabinet. Fraser went to Fisheries and Carney to Energy – two significant portfolios. Carney was the first woman from B.C. to lead a department (Campagnolo was a Minister of State).

Fraser would resign halfway through the first term during “Tunagate”, as scandal concerning rancid tuna, but his stature among MPs led him later to election, and much-dignified reign, as Speaker of the House of Commons. Overall, Fraser served in the House from 1972-1993.

Carney would move to International Trade during the dramatic US-Canada Free Trade negotiations. She did not run again in 1988 (and, later on, appointed to the Senate where she was an outspoken member). Tom Siddon would replace Fraser, and others like Gerry St. Germain, Frank Oberle, and Mary Collins would ultimately join Mulroney’s cabinet.

St. Germain was a Mulroney favourite. The bilingual, Metis chicken farmer was my Member of Parliament in Mission-Port Moody. He entered Parliament with Mulroney following a pair of 1983 by-elections. He was also my opponent when, as a teenager, I rode my ten-speed bike down to Liberal Mae Cabott’s campaign office on the Lougheed Highway in 1984.

St. Germain was a Mulroney favourite. The bilingual, Metis chicken farmer was my Member of Parliament in Mission-Port Moody. He entered Parliament with Mulroney following a pair of 1983 by-elections. He was also my opponent when, as a teenager, I rode my ten-speed bike down to Liberal Mae Cabott’s campaign office on the Lougheed Highway in 1984.

Losing big to Gerry taught me an early lesson in humility (Tip: be careful burmashaving on a busy highway when everyone hates your political party, and they are not telling you that your party is #1 when they use their middle finger).

In 1986, I found myself looking for a seat to Question Period in Ottawa and contacted my local MP, Gerry. With great gusto, Gerry led me through the back halls of Parliament proclaiming, “Let me show you what a Tory can do for a Grit.”

Gerry became National Caucus Chair in 1984, a huge responsibility considering it remains the largest caucus in Canadian history. He was elevated to cabinet during that term, but, incredibly to me, Gerry lost his seat in 1988 at the very moment he was poised to move up into the senior cabinet ranks. He would have been the senior B.C. minister with huge clout. BCers often choose protest over pragmatism. He would be appointed to the Senate, serve as president of the Progressive Conservative Party in the dark years, and be an early mover on bringing the PCs and Reform/Alliance parties together.

A B.C. prime minister… briefly

In 1988, Pat Carney’s retirement created a vacancy in Vancouver-Centre. Back then, Progressive Conservatives were electable in that riding, seemingly unimaginable today. Kim Campbell resigned her seat in the provincial legislature part way through her first term, secured the PC nomination, then won the seat, and was catapulted into Cabinet. She was another rarity – a french-speaking British Columbian. As Justice minister (then National Defence), she held a high national profile, and emerged as the consensus favourite to succeed Mulroney following the demise of the Charlottetown Accord. Campbell fended off Jean Charest for the leadership win.

Kim Campbell on the campaign trail, 1993

She had a strong B.C. network behind her, like Chief of Staff Ray Castelli and other apparatchiks that have been a big part of federal politics from B.C., but Mulroney did not leave her much time to make her own mark and the subsequent election played out for her like it did for John Turner in 1984, except worse. The party was decimated and, like 1984, Vancouver bore witness on election night to a humiliating concession speech by a sitting prime minister. Unlike Turner, Campbell lost her own seat.

Jean Chrétien’s election in 1993 and subsequent cabinets through 2003 had consistent B.C. representation (unlike PET from 1980-84), yet it was not at the heaviest of heavyweight levels. David Anderson, first elected in 1968, before switching to provincial politics to lead the B.C. Liberals, returned from the political wilderness in 1993 to serve as National Revenue Minister before moving on to Fisheries, then to his signature role in Environment. Herb Dhaliwal was another prominent minister during the Chrétien era, following Anderson in National Revenue and Fisheries before going to Natural Resources. Ministers of State included former B.C. ombudsman Stephen Owen, Richmond MP Raymond Chan, and Vancouver-Centre MP Dr. Hedy Fry. Chrétien could never elect more than 6-7 from B.C. so he didn’t have a lot of MPs to choose from. Moreover, about 99% of the MPs during his years as prime minister from Ontario were Liberal, therefore, B.C. was vastly outnumbered in the Liberal caucus. The influential non-minister during that time was Senator Ross Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick was a Chrétien confidante who backed him during the 1984 and 1990 leadership campaigns, and called the shots in B.C. for the general election campaigns.

B.C.’s return to Diefenbaker-like prominence: 2004-2011

I’ll run for the Liberals in 2004, says ex-NDP Premier Ujjal Dosanjh

Both the Paul Martin cabinet and early Stephen Harper cabinets saw a decided uptick in B.C. clout at the federal cabinet table. Following the 2004 election, Martin appointed a record five B.C. ministers including star recruits David Emerson (Industry) and former B.C. NDP Premier Ujjal Dosanjh (Health). The lineup was rounded out by Stephen Owen, Raymond Chan, and Senate Leader Jack Austin. The B.C. delegation was aided by a regional campaign, led by Mark Marissen, that punched above its weight in the 2004 election with its “Made in B.C. Agenda”. The Liberals won more seats in B.C. despite dropping from a majority to a minority. (They would win more again in 2006 in a losing national effort)

Stock

Harper’s first cabinet contained a major surprise – David Emerson. To the astonishment of Liberals and Conservatives alike, the Liberal star switched jerseys, eschewing politics for policy, and assumed the International Trade portfolio and eventually Foreign Affairs before he left office in 2008. Emerson was recruited to Harper’s cabinet by outgoing MP John Reynolds. Reynolds served in the House of Commons from B.C. ridings on two occasions (1972-77 and 1997-2006). In between, he was a Social Credit MLA from 1983-1991, serving as a cabinet minister and Speaker. Reynolds acted as interim Leader of the Official Opposition, turning over the reins to Stephen Harper. In 2006, Harper appointed Reynolds to the Privy Council.

Emerson was joined from B.C. by former Canadian Alliance leader Stockwell Day (Public Safety, International Trade, Treasury Board). A former Alberta Finance Minister, Day was a B.C. MP by virtue of running in a by-election in the Okanagan upon becoming leader. He stayed put and became an influential B.C. minister. Day was also an important interlocutor between the Harper government and the nascent Christy Clark government in 2011, helping build a cohesive relationship at a sensitive time.

Chuck Strahl (Agriculture, Indian and Northern Affairs, Transport), and Gary Lunn (Natural Resources) rounded out Harper’s first cabinet. Jay Hill’s appointment in 2007 as Whip (elevated to cabinet) then Government House Leader would make it five ministers for the B.C. delegation, matching Martin. B.C. had considerable clout.

Fading out of the Harper years

Emerson, Day, Strahl and Hill would all choose to leave politics by 2011, and Lunn involuntarily when he lost to Green Party leader Elizabeth May. They would give way to James Moore, who started in Heritage and went to Industry, becoming the face of the government in B.C. during the final Harper term. Ed Fast, in International Trade, North Islander John Duncan who served in Aboriginal Affairs & Northern Development, then-Delta MP Kerri-Lynne Findlay, and Richmond Centre MP Alice Wong all served in the final term. As the Harper mandate struggled in its final years, so too did its profile in British Columbia – not an uncommon life cycle for aging governments.

A new team in 2015

The appointment of JWR

Justin Trudeau only had two incumbents from B.C. heading into the 2015 election, but neither were invited into his first cabinet. Instead, he went with new blood that aligned with Liberal political priorities. Three ministers were appointed, all newcomers to Parliament Hill. Jody Wilson-Raybould was a historic choice as Justice Minister – the first indigenous Justice Minister. She followed in the footsteps of Kamloops indigenous MP Len Marchand who served in PET’s cabinet. Joining Wilson-Raybould in the ranks of senior cabinet was Vancouver South MP Harjit Sajjan, appointed as Minister of National Defence, a post he kept for the entirety of the first term. Delta MP Carla Qualtrough joined cabinet as Minister of Sport and Persons with Disabilities. While

Harjit Sajjan: senior post from day one

Wilson-Raybould and Sajjan were in the upper tier of cabinet, the Trudeau government took a different term in equating senior cabinet ministers with regional clout. There was no “B.C. minister”, the traditional model where a minister is the “go-to” between the federal government and the province and its stakeholders. Backed by a Ministers’ Regional Office, this role has informal influence and is where a lot of regional brokering would take place. Instead, it appeared JWR and Sajjan focused on their considerable cabinet duties, freed from the political responsibilities coming from a regional boss role.

Carla Qualtrough: moved up the ladder

Qualtrough emerged as a steady player and was elevated to Minister of Public Works in 2017. Colleague Jonathan Wilkinson was recruited to cabinet in 2018 as Minister of Fisheries & Oceans, a vexing role which many previous B.C. MPs have performed. With four full ministers, B.C. enjoyed a solid presence in cabinet despite the absence of a traditional regional minister role.

Then in 2019, everything changed. The controversy surrounding JWR and the prime minister is well documented. An early 2019 cabinet shuffle moved JWR from Justice to Veteran Affairs. Sparked by the resignation of cabinet minister Scott Brison, the shuffle ignited tensions that culminated in JWR’s resignation from cabinet, then her removal from caucus. Like H.H. Stevens, she sought re-election after parting ways, and won her Vancouver seat. For several months, JWR’s future with the Liberals hung in the balance. Today, she moves forward as an independent, and who knows what else.

Her departure created an opening for longtime Vancouver-Quadra MP Joyce Murray, a former provincial cabinet minister. Murray took the helm at Treasury Board in spring 2019, keeping a low profile.

Jonathan Wilkinson with the prime minister: Saskatchewan roots may be called upon in next term of office

As Prime Minister Trudeau puts in place his cabinet picks on November 20th, he may well stay the course with Sajjan, Wilkinson, Qualtrough, and Murray, though one would think that roles will change for most of them. They were all re-elected, and contribute to the gender balance that the prime minister says will be maintained. Perhaps B.C. will gain more influence because of the absence of Liberal MPs in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

There are now 11 Liberal MPs from British Columbia. Trudeau will also be able to consider Terry Beech, Sukh Dhaliwal, Ken Hardie, Randeep Sarai, Patrick Weiler, and the indomitable Hedy Fry. All Liberal MPs are from Metro Vancouver, meaning no opportunity for the Island or the Interior to have a voice in cabinet.

Eclipsed by other regions

For many Liberal governments in the Pearson-Trudeau-Chretien eras, it was often a case of being “west of the best” or so it seemed. B.C. had many capable ministers during this time but very few national personalities that one hearkens back to when remembering an era. Ron Basford may have the strongest claim for cabinet legacies. The Martin government went in a stronger direction for B.C. but its lifespan was short. Harper’s team started off strong but B.C.’s collective influence seemed to fade down the stretch.

Conservative cabinets have seen B.C. eclipsed by Conservative-crazy Alberta, which has established the storyline for much of the past 40 years. Alberta had leader (1976-83) and Prime Minister Joe Clark (later Secretary of State for External Affairs and lead constitutional negotiator) and Deputy Prime Minister Don Mazankowski. The demise of the PCs was born in Alberta too with Preston Manning’s Reform Party. The evolution and return of the conservative movement was an Alberta story – Stockwell Day (who ran for leader of the Alliance from Alberta before moving to B.C.) and Stephen Harper led in succession. Harper’s cabinet also featured prominent Albertan personalities such as Jim Prentice, Rona Ambrose (an interim leader), and Jason Kenney, now the Premier of Alberta. Neighbouring Saskatchewan produced Andrew Scheer, who won all but one seat in Alberta and Saskatchewan in 2019. B.C.’s political climate is much more competitive, though conservatives usually emerge with a plurality of the votes federally, restraining the election of Liberal MPs and pool of available cabinet talent when the Liberals rule (which has been most of the time).

British Columbians have risen to prominence in the NDP, although not usually to the top. Tommy Douglas led the party from a base in B.C. for a time. Rosemary Brown, Dave Barrett, Svend Robinson, and Nathan Cullen have all been serious national leadership contenders, though unsuccessful. Current leader Jagmeet Singh represents a B.C. riding. Are they any closer to the cabinet table? No, they have been getting further and further away since Jack Layton’s high point in 2011.

B.C.’s Burden

Why does B.C. lack clout?

Distance. How many people want to fly 3000 miles back and forth each week? Time spent traveling is enough to dissaude anyone, especially those with younger children.

Under-representation. A point of regional unfairness is that B.C. ridings have more population than most provinces due to Canada’s constitution and constitutional side deals. The vast expanse of Skeena has far more constituents than ridings in Saskatchewan, Manitoba or any in the Maritimes. How does that make sense? It makes a tough job even tougher.

Political culture. Federal politics is more abstract to British Columbians. BCers do not live and die by federal politics. There is very little media coverage of B.C. politicians on Parliament Hill (JWR controversy excluded). Provincial politics is the main sport and drives the media’s and the public’s interest.

Protest over politics. We have often gone the other way when Canadians elect their governments. B.C. abandoned PET in 1980, cut down the PC team in 1988, and kept Chretien on a short leash.

Political network. It’s tough to aspire to national leadership when the critical mass is elsewhere. Kim Campbell remains the only B.C.-raised prime minister. Alberta has figured out how to gain national office, but no one here. H.H. Stevens may have had the first good chance in the dying days of the RB Bennett government but he passed on it. E. Davie Fulton was a thorn in Diefenbaker’s paw, but finished third to Dief in the 1956 PC leadership, and third again trying to succeed him in 1967. John Fraser tried in 1976. Hedy Fry and Joyce Murray both made quixotic bids to lead their parties but were never in contention. Is there a B.C. contender to replace Andrew Scheer, if there is an opening? Hard to see.

Bilingualism. Fewer B.C. politicians speak french than in eastern provinces. This has been a drawback in climbing the greasy pole. James Moore does, and he had a good run, but he is an exception.

The challenge appears to be even greater for MPs outside the Vancouver area. Most ministers, as this is where Liberals usually get elected, have been fairly close to the province’s largest city. The B.C. Interior and Vancouver Island have lacked significant cabinet representation over time, and will lack representation again in the coming term.

Prime ministers have been piled up like cordwood from Quebec, Ontario, and Alberta. Even Saskatchewan has had its run; B.C. has but one brief stint from one of its own prior to her electoral slaughter. Where have been the Finance Ministers from B.C.?

Many excellent ministers from B.C. have served at the cabinet table, but my overall assessment is that we, as a province, haven’t been exceptional in the federal arena. In part, because many have chosen not to run.

What’s next?

On November 20th, a new cabinet will be chosen and a new chapter will begin on B.C.’s role at the cabinet table. While Justin Trudeau lacks representation in Alberta and Saskatchewan, he can at least draw from an 11-member caucus in B.C. This is the second largest Liberal caucus from B.C. since 1968 – that’s not saying much, but it’s a lot better than 1980 when his father did not have an elected member west of Winnipeg.

A key sign to watch for B.C.’s clout will be whether the regional minister system is re-established, providing a more direct portal for B.C. interests to interact with the federal government. Ottawa is a long way away from B.C. It will help our issues and our interests if Ottawa is brought closer.

** This post was taken from a number of sources and not always easy to piece together B.C.’s federal voice. If there are any sins of omission or commission, please comment. Thank you.

Related

.jpg)

It was a huge mandate. “Red Tories” John Fraser and Pat Carney, an upset winner over Art Phillips in 1980, led the B.C. contingent in cabinet. Fraser went to Fisheries and Carney to Energy – two significant portfolios. Carney was the first woman from B.C. to lead a department (Campagnolo was a Minister of State).

It was a huge mandate. “Red Tories” John Fraser and Pat Carney, an upset winner over Art Phillips in 1980, led the B.C. contingent in cabinet. Fraser went to Fisheries and Carney to Energy – two significant portfolios. Carney was the first woman from B.C. to lead a department (Campagnolo was a Minister of State). St. Germain was a Mulroney favourite. The bilingual, Metis chicken farmer was my Member of Parliament in Mission-Port Moody. He entered Parliament with Mulroney following a pair of 1983 by-elections. He was also my opponent when, as a teenager, I rode my ten-speed bike down to Liberal Mae Cabott’s campaign office on the Lougheed Highway in 1984.

St. Germain was a Mulroney favourite. The bilingual, Metis chicken farmer was my Member of Parliament in Mission-Port Moody. He entered Parliament with Mulroney following a pair of 1983 by-elections. He was also my opponent when, as a teenager, I rode my ten-speed bike down to Liberal Mae Cabott’s campaign office on the Lougheed Highway in 1984.