With just over five months from the start of the next provincial election, are we at a point where BC’s political landscape is about to be reshaped?

The BC Liberals won the popular vote six times in a row from 1996 to 2017 but that brand has been discarded. Its successor brand, BC United, has fragmented with two MLAs defecting to the upstart BC Conservatives, and many of its voters parked there too – the amount differs depending on which poll you’re looking at. Regardless of the exact numbers, it is crystal clear that there is a vote split. Electoral coalitions are tough to maintain, but the math is grim when they fall apart. To paraphrase Ben Franklin, it’s ultimately a question of “hanging together or hanging separately”.

What does history tell us?

The re-formulation of BC’s ‘free enterprise coalition’ – or as one astute political observer calls it the “Not NDP” coalition – has followed ‘big bang’ political events on four occasions over the past 83 years. Once a big bang happens, the voters are presented a revised option to challenge the dominant left-wing option, originally the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and, after 1961, the BC NDP.

The big bangs have taken place in a variety of ways – a deal between parties (1941), the voters choosing a surprising new direction (1952 and 1991), and coalition by migration when MLAs and partisans from weaker parties moved over to support the stronger party in order to remove a vote split (1975).

Let’s Make a Deal

In 1941, fresh after a disappointing election campaign where his majority government was reduced to a minority, Liberal Premier Duff Pattullo, who had led BC since 1933, wanted to carry on as usual. Concerned by the increasing strength of the left-wing Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), Pattullo’s cabinet and caucus colleagues wanted to join forces with the Conservatives and form a wartime coalition government. Pattullo dug in. Frustrated, Liberal cabinet ministers resigned, including Finance Minister John Hart. On December 2nd, 1941, at a special convention of almost 800 Liberal members held at the Aztec Room in the Hotel Georgia, both sides of the argument were heard over the course of a four-hour debate with those favouring coalition prevailing over Pattullo’s point of view, by a vote of 477-312. Pattullo resigned as party leader and declared, “You have given your verdict, which I accept. But you must remember you are now no longer Liberals – you are coalitionists.” He stepped down from the platform, waving to the crowd, saying, “Good-bye, boys and girls” and walked into the night. (see Robin Fisher’s, Duff Pattullo of British Columbia). John Hart was elected immediately by the Liberal rank and file to lead the party, and, within the week, was installed as the Coalition premier. Conservatives were brought into cabinet, with party leader, Pat Maitland, becoming Attorney-General. In the subsequent election, Liberals and Conservatives held joint nomination meetings where an equal number of members from each party were eligible to choose an agreed-upon coalition candidate at the riding level.

The Voters Choose a New Direction

In 1952, voters were tiring of the coalition parties. In fact, Liberals and Conservatives were tiring of each other. After two consecutive majority wins in 1945 and 1949, the coalition parties decided to resume hostilities and run their own candidates, with one key wrinkle – they hatched a plan intended to thwart the CCF by bringing forward a single transferable ballot where voters marked their first, second, and third choices. The thinking was that Liberal and Conservatives would gang up by being each other’s second choice thus denying the CCF a chance to otherwise win under the traditional ‘first past the post’ system. What they did not envision was the Social Credit Party, which governed Alberta but heretofore a non-factor in BC, becoming a plausible option for many voters. The Socreds trailed the CCF after the first count of ballots by a margin of 7 seats, but when second and third choices were counted, they edged ahead of the CCF, with 19 of 52 seats in the Legislature (the CCF had 18). The Socreds, who were actually led by an Albertan during the campaign, did not have an elected leader until after the campaign when W.A.C. Bennett (a former Conservative MLA who went Socred before the election) was chosen by the newbie caucus. W.A.C. then had to twist the arm of the Lieutenant-Governor to be invited to form a government. It worked out – he governed for 20 years on the strength of seven consecutive election wins, and shrewdly did away with the single transferable system after 1953.

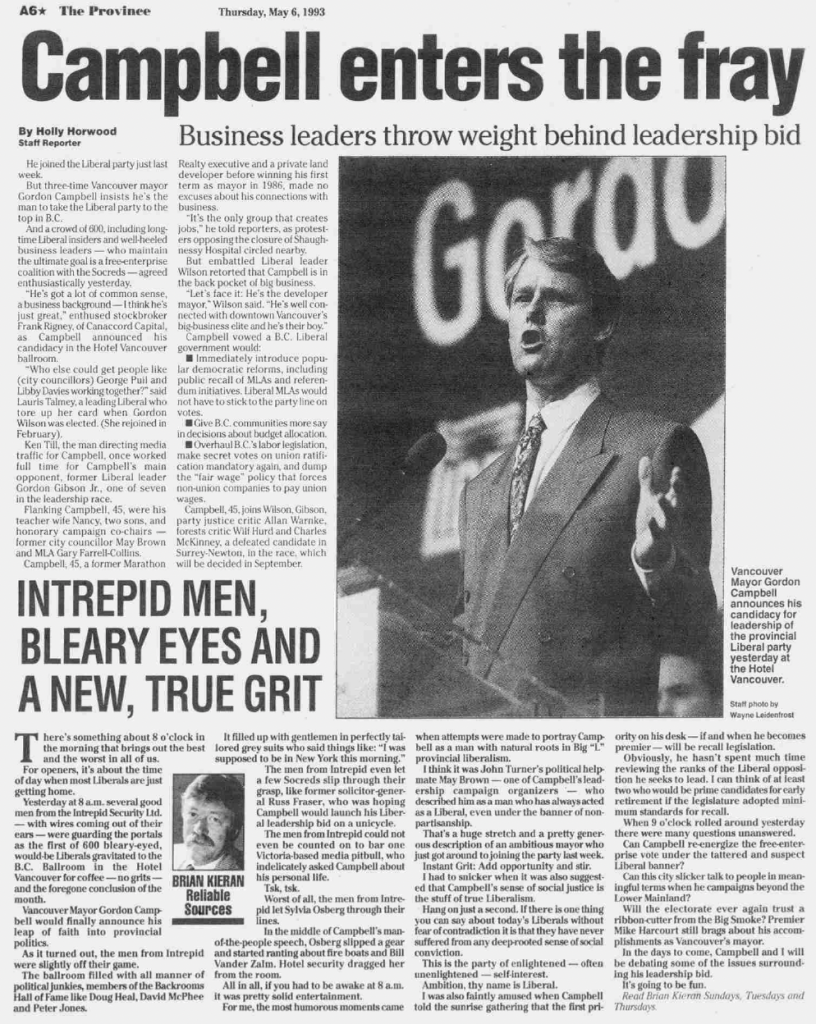

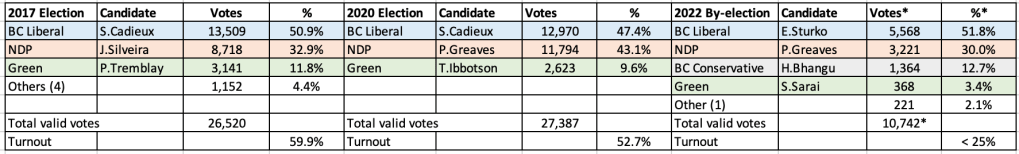

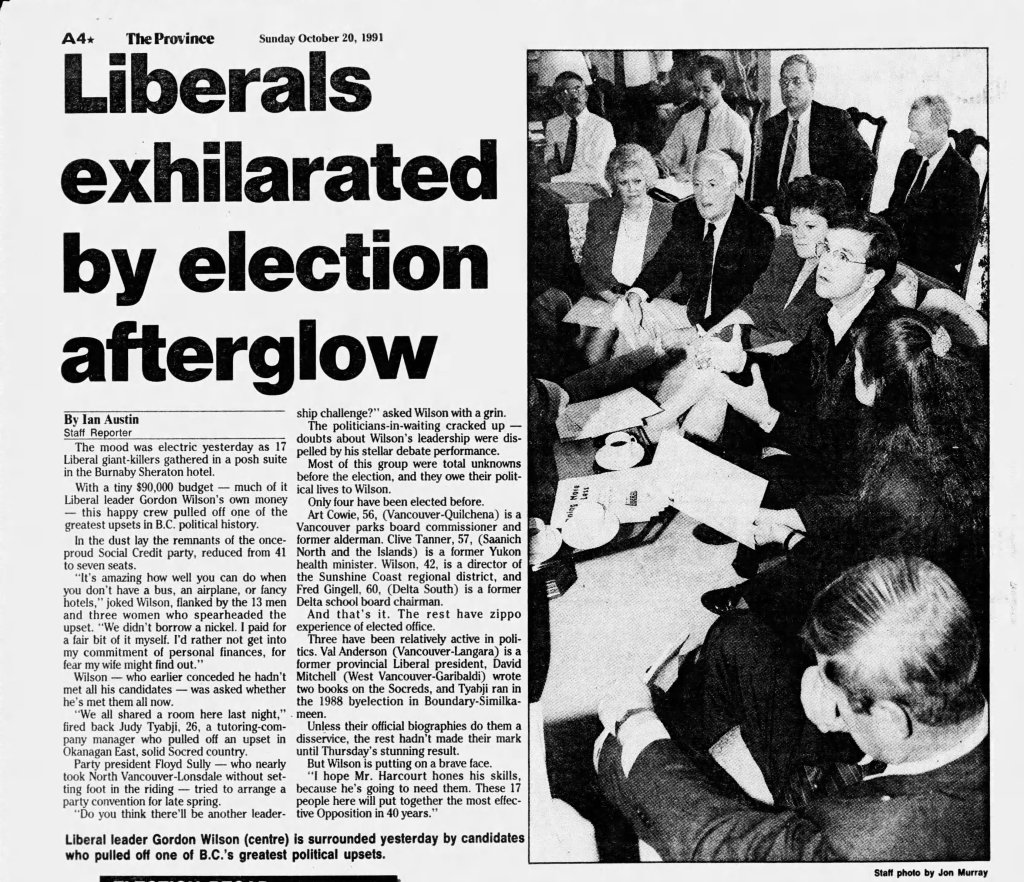

In 1991, the voters would take matters into their own hands again and shake up the political landscape. They had had enough of the Social Credit Party, reducing the dynasty that had governed for 36 of the 39 previous years to only seven seats in the 69-seat Legislature. The BC Liberals literally rose from the ashes under leader Gordon Wilson to jump from zero to 17 seats and claim the Official Opposition, while the NDP steered its way to a majority government under Premier Mike Harcourt. The Liberals would metamorphosize in the years that followed. Wilson lost his grip on the leadership leading to a convention where the three Gordons faced off – Wilson, former leader Gordon Gibson, and Vancouver mayor Gordon Campbell. Campbell prevailed and set forth to rebuild the BC Liberals – then mainly a ‘liberal’ party – by attracting new blood, including ex-Socreds, Progressive Conservatives, and federal Reformers. It would take a decade. A close loss in 1996 (due to a vote split with remnants of the Socreds under the banner of Reform BC) was followed by an electoral landslide in 2001 when Campbell’s BC Liberals won 77 of 79 seats. The BC Liberal new era in government would run for 16 years to 2017 when a razor thin, combined NDP-Green majority ousted them in a confidence vote. John Horgan was propelled into power on the strength of a 189 vote NDP win over the BC Liberals in Courtenay-Comox, where the BC Conservative candidate had a coalition-killing 2,200 votes.

Coalition by migration

In 1972, the NDP, led by Dave Barrett, formed government for the first time, aided greatly by the rise of the BC Conservative Party which went from about zero to over 12% of the vote, creating a deadly vote split. In a Kelowna by-election to fill W.A.C. Bennett’s seat in 1973, the leader of the Conservatives, Derrill Warren, faced W.A.C’s son, Bill Bennett, the Socred candidate. Bennett the younger prevailed, dispensing with the Conservatives, soon became leader of his party, and ultimately attracted three Liberal MLAs (including former leader Pat McGeer) and one Conservative MLA to cross to him. The four floor crossers would become senior cabinet ministers after the election. Other key partisans, like former BC Liberal leadership candidate Bill Vander Zalm, jumped to Bill Bennett’s side. It wasn’t just as simple as that, though – the floor crossings followed months and months of public discussions of a ‘Unity Party’ by various opposition MLAs and advocacy by a third-party group – the Majority Movement – that pushed for a united front (Professor Gerry Kristiansen writes a great summary of events in BC Studies). Ultimately, the consolidation of seats under the Socreds sent the political ‘bat signal’ to free enterprise voters that the Social Credit banner had been rejuvenated, and they won the 1975 election decisively, and went on to govern for another 16 years. The Liberal and Conservative vote collapsed. The NDP vote was virtually unchanged in 1975 but they couldn’t defeat a unified opposition.

After the 1996 election when the BC Liberals won the popular vote but lost the election primarily due to a vote split with BC Reform, ‘Coalition by Migration‘ was effected to solidify support as Reform MLA Richard Neufeld crossed the floor to the BC Liberals (later to serve in cabinet) along with a past party president, and many grassroots members. BC Reformers were effectively wooed by the BC Liberals and room was made in the coalition tent for them. This process was repeated again in 2011-2013 era as Christy Clark moved to shore up the BC Liberal coalition by bringing key federal Conservative leaders onside to head off a BC Conservative comeback, convening ‘Free Enterprise Friday’ at its party convention, and notably recruiting former BC Conservative by-election candidate John Martin to run as a BC Liberal in the 2013 general election.

Fast forward to 2024.

We’re due for a Big Bang, whether that’s before or after the October election.

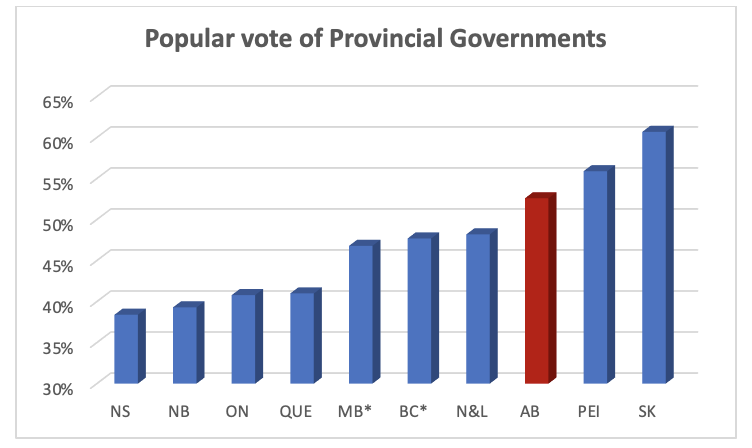

Will the parties hold their ground and have the voters choose their destiny for them? Will one of the opposition parties conclusively pull away from the other and turn the election into a two-way race or will they hold each other back and pick up the pieces afterward? As the 1991 example showed, it took a decade for a ‘free enterprise’ alternative to return to power – winning seats is one thing, but, depending on the scenario, the learning curve of brand new MLAs with no legislative experience is quite another. Just because a new option prevails doesn’t mean it’s going to govern anytime soon. It must still have the ability to appeal to more than 40% of the electorate, which is what successful coalitions have been able to do by attracting a broad spectrum of voters.

Alternatively, will the action take place pre-election, whether that’s a brokered deal that includes joint nomination meetings and agreed-upon candidates, similar to 1941 scenario, or party insiders stampeding one way or another as was the case in 1975? And how would the voters react to that? Would they be turned off by backroom maneuvers or energized that there may be a real horse race?

We’ll see. As Mark Twain said, “History never repeats itself but it often rhymes.”

Catch up with Mike McDonald, Kate Hammer, and Geoff Meggs weekly on Hotel Pacifico, your Five Star podcast designation for B.C. politicos.

More …