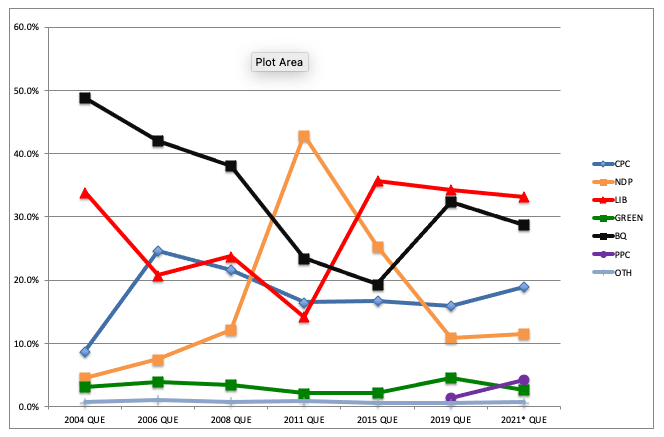

British Columbia will be fascinating to watch on election night. As advance polls open, there has been a struggle between the Liberals and Conservatives to emerge as a clear leader, while the NDP appear to be on the move post-debate. The Greens maintain a strong presence on the Island that could be converted into a bushel of seats.

When you see these poll numbers bouncing around, how do they convert to seats? I thought it would be ‘fun’ to play with numbers today.

Four parties (and an independent) in the hunt for seats in BC. It’s that close, it seems.

In ‘BC Battleground’, I wrote about the key regions. In particular, the Lower Mainland outer suburbs and Vancouver Island are very volatile.

A political sniffle can lead to an electoral coma for parties mired in three and four way battles.

When we forecast results, they are based mainly on the result of the last election, adjusted to potential 2019 scenarios. When it’s all said and done, the seats normally follow a similar pattern. The ranking of seats, party by party, doesn’t usually shift that much from election to election (a party’s best and worst seats tend to be consistent, such as the NDP in East Van, CPC in Peace River, or Liberals in Quadra). Over time, yes, coalitions shift and parties evolve, winning in places that are new, and losing in places that used to be strongholds. That pattern usually takes a few cycles.

Assuming patterns are fairly consistent to 2015, we can look at how seat totals might play out based on popular vote. This does not take into account special local factors.

Reminder that in 2015, the seat totals in BC were:

- 17 Liberal

- 14 NDP

- 10 CPC

- 1 Green

Scenario 1: Three-way tie, with Greens trailing in fourth

|

CPC |

Lib |

NDP |

Green |

| Vote% |

26.5% |

26.5% |

26.5% |

16.0% |

| Seats |

12 |

13 |

16 |

1 |

Despite the three-way tie in popular vote, the NDP has an efficiency advantage, mainly based on winning, like they did in 2015, six of seven seats on the Island with about one-third of the vote.

Scenario 2: Top 2 CPC and Liberals, NDP third, with Greens trailing in fourth

In 2015, the Liberals won popular vote in BC by 5.5%. This scenario has the CPC tying the Liberals, with NDP trailing by about same amount as 2015.

|

CPC |

Lib |

NDP |

Green |

| Vote% |

28% |

28% |

23% |

16.0% |

| Seats |

14 |

14 |

12 |

2 |

Both Conservatives and Liberals vote breaks evenly into seats with NDP punching above its weight due to the Island.

Scenario 3: CPC lead over Liberals, NDP third, Greens trailing in fourth

If the Conservatives take a 4-point lead over the Liberals, the math starts to move.

|

CPC |

Lib |

NDP |

Green |

| Vote% |

30.0% |

26.0% |

23% |

16.0% |

| Seats |

17 |

11 |

12 |

2 |

Seat pick ups increase in the outer suburbs of Vancouver for the Conservatives, levelling that region which the Liberals dominated in 2015. The Liberals would hold most of their Vancouver-urban core seats.

Scenario 4: Liberals lead Conservatives, NDP third, Greens fourth

Scenario 3 is flipped to a Liberal 4-point lead, holding the NDP and Greens constant.

|

CPC |

Lib |

NDP |

Green |

| Vote% |

26.0% |

30.0% |

23.0% |

16.0% |

| Seats |

10 |

17 |

13 |

2 |

Scenario 5: NDP falters, Greens rise

The previous four scenarios have the Green constant at 16%. This scenario moves them to 20% and the NDP to 22%.

|

CPC |

Lib |

NDP |

Green |

| Vote% |

27.0% |

27.0% |

22.0% |

20.0% |

| Seats |

14 |

14 |

10 |

4 |

The Island is very dynamic in terms of vote splits. If the Greens rise over there (with 20% province-wide indicating a popular vote on the Island of over 35%), then NDP seats fall to the Greens, at least on the Lower Island.

Scenario 6: One party blowout

It would take a 10%+ lead in the popular vote for any one party to grab 50% of the seats (21 seats).

Blue crush

|

CPC |

Lib |

NDP |

Green |

| Vote% |

35.0% |

24.0% |

22.0% |

15.0% |

| Seats |

22 |

9 |

9 |

2 |

Big red machine

|

CPC |

Lib |

NDP |

Green |

| Vote% |

24.0% |

35.0% |

22.0% |

15.0% |

| Seats |

5 |

23 |

12 |

2 |

Jagmentum

|

CPC |

Lib |

NDP |

Green |

| Vote% |

24.0% |

24.0% |

33.0% |

15.0% |

| Seats |

9 |

11 |

21 |

2 |

Green armageddon

|

CPC |

Lib |

NDP |

Green |

| Vote% |

15% |

15% |

15% |

50% |

| Seats |

0 |

0 |

0 |

42 |

I mean, isn’t Green armageddon just inevitable? Who doesn’t want unicorns and rainbows?

Local factors

The seat modelling ignores that Paul Manly won the Nanaimo-Ladysmith by-election for the Greens, that the Conservatives fired their Burnaby-North Vancouver candidate, that the Liberals fired candidates in Victoria and Cowichan last election, thus lowering their base for this model. It also does not account for a candidate by the name of Jody Wilson-Raybould. So, yes, local factors can confound the model, but the model overall speaks truth. Due to our system, the votes have to land somewhere. When you see fortunes rise and fall in the polls, the seats will follow.

It seems that close. We’ll see which scenario prevails.

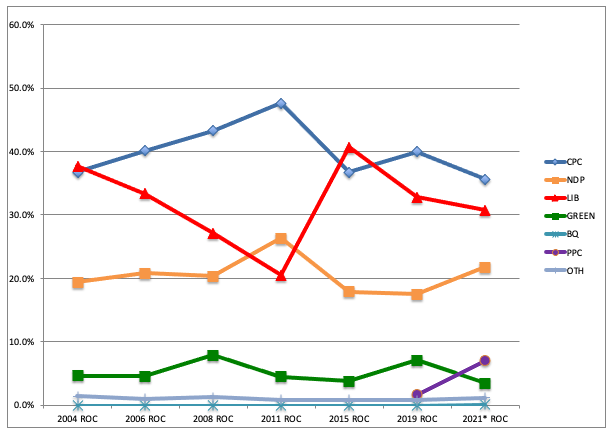

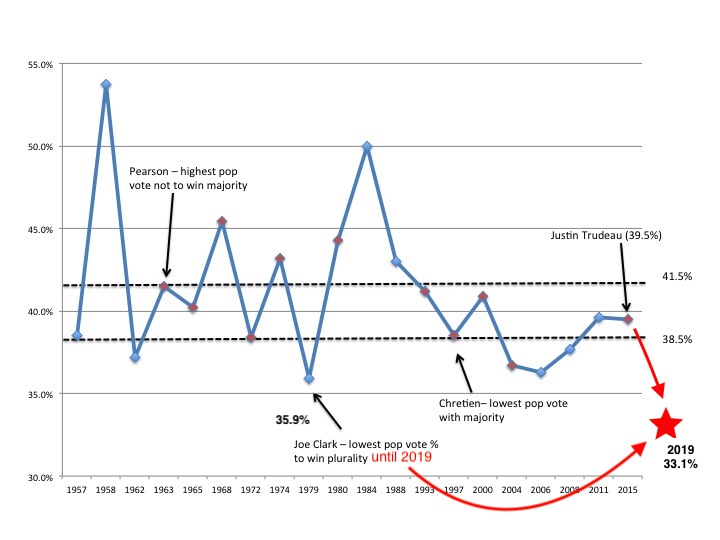

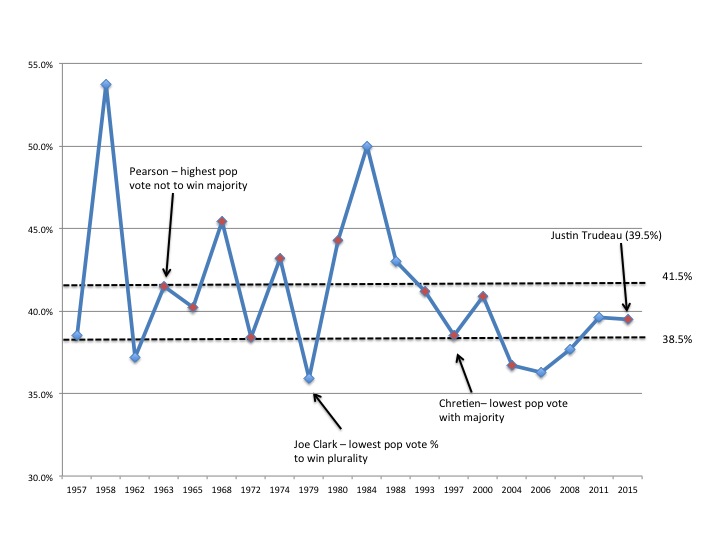

In fact, only Lester Pearson’s Liberals were unlucky enough to be above the 38.5% mark and not win a majority – in consecutive elections too. John Diefenbaker’s Progressive Conservatives were on the 38.5% line in 1957 and missed out on a majority that time. In 1958, he took care of business with a majority of seats and votes.

In fact, only Lester Pearson’s Liberals were unlucky enough to be above the 38.5% mark and not win a majority – in consecutive elections too. John Diefenbaker’s Progressive Conservatives were on the 38.5% line in 1957 and missed out on a majority that time. In 1958, he took care of business with a majority of seats and votes.