The Conservatives will be electing a new leader prior to the next federal election and, who knows, maybe the NDP too.

When it comes to electing Leaders, BC might as well stand for “Barely Chosen”.

I recently wrote on BC’s place in Cabinet since Confederation. Now, I’ve turned my attention to our place at the head of the table.

In Canada’s history, I count 58 people who have led one of the contending national parties – Liberal, Conservative (including PC, Reform, Alliance), and CCF/NDP. Only 23 became prime minister.

Of those 58, I count only three British Columbians among them.

Rt. Hon. Kim Campbell remains the only BC-born and raised leader to win a national leadership among the three major parties since parties (not caucuses) began electing leaders.

Not many British Columbians have their painting hanging in the Parliament Buildings

For the purpose of my analysis below, I’m designating John Turner as a British Columbian too. Well, he has to belong somewhere, and given that he spent his early years in Rossland, was a star student and athlete at UBC, and sought election in Vancouver-Quadra twice as a Leader, I claim him as a British Columbian. Aside from Campbell and Turner, BC’s performance in national leadership races has been very spotty.

Hold on, we do get in the back door sometimes. Hon. John Reynolds served as Leader of the Opposition for the Canadian Alliance when Stockwell Day stepped down. By my math then, three British Columbians have served as Leaders (elected or otherwise) in the past 148 years.

Then there are some on the bubble. Stockwell Day? He has as much claim to being a British Columbian perhaps as John Turner. He spent some his early years in BC and represented BC ridings as leader, yet for the purpose of this analysis, I’m classifying him as Albertan given that he was fresh from serving in the Alberta Cabinet. He might quarrel with that.

Deborah Grey also spent early years in BC, is related to former BC Premier Boss Johnson, and lives in BC now. She served as Leader of the Opposition, in between Preston Manning and Stockwell Day. But she was clearly representing Alberta at that time.

Liberals in BC might claim Justin Trudeau with his BC grandparents and work experience in the province, but you would have to put him in the Quebec column.

Then there’s John A. who represented Victoria for four years as prime minister, but, look, since he hadn’t built the railroad yet, he didn’t even see his riding so, no, he doesn’t count.

I’m tempted to add the federal Social Credit into this analysis to pump up BC’s numbers. They had an interim leader from BC in the 1960’s. Maybe the Greens should be considered too, but let’s stick to the major parties. I don’t have all day here, and neither do you.

Therefore, that’s three leaders from BC, none elected in a general election as Leader. That compares to 17 leaders from Ontario, 13 leaders from Quebec, 7 from Alberta and Nova Scotia. The Yukon is breathing down our neck with 2 leaders.

When the time a BC Prime Minister has been in office compared to other provinces, it’s a bit humbling. BC is at < 1 year combined (Turner and Campbell) while Quebec is 60+ years and counting. Our neighbour, Alberta, has had three elected prime ministers elected totalling about 15 years.

Some might argue this type of analysis is pointless since national leaders embody more than their home-province. In some cases, they are very much pan-Canadian and hard to peg regionally. However, history does illustrate the challenge facing BC-based leaders.

The focus of this piece is regional, but it’s important to note that only 5 of 58 leaders have been women. Three were NDP – Audrey McLaughlin, Alexa McDonough, and Nycole Turmel. Two Conservatives: Kim Campbell and Rona Ambrose. The Liberals have yet to elevate a woman as leader.

The following table shows the leaders (elected and interim) by province by parties.

Table 1: Leaders by party and province, as I see it:

Did I miss any? I bet you might be wondering who some of these people are that I have listed in the table above. Some of the interim leaders are fairly obscure but, in their time, were important figures and judged by their colleagues to have the gravitas to lead their party in a troubled time, usually after death or a defeat:

- Daniel MacKenzie from Cape Breton took over the helm of the Liberal Party upon Sir Wilfred Laurier’s death and contested the leadership against MacKenzie King, which he lost. Hazen Argue acted as interim leader before losing a subsequent leadership convention to Tommy Douglas (Argue left for the Liberals shortly thereafter).

- There’s Richard Burpee Hanson, a former Mayor of Fredericton and Trade Minister in the RB Bennett government, who served as interim leader after the Conservatives were trounced in the 1940 election. Not exactly a household name.

Richard Burpee Hanson: “I’m fading into history much like this photo”

He gave way to the comeback-kid Arthur Meighen when he returned to national politics after serving as PM twice in the 1920s. But Hanson had to stick around longer when Meighen lost a by-election, ending his brief return. New Brunswick’s other leader, Elsie Wayne, also served as an interim when Jean Charest left the post of PC leader to lead the Quebec Liberal Party.

My brother was Leader ???

- Erik Nielsen (“velcro lips”) was the first leader of a major political party from the North and was also a major force in the early years of Brian Mulroney’s government. He was the brother of famous actor Leslie Nielsen (if you’re a Millennial, go see Airplane).

Rona Ambrose joins this illustrious list. She may not be there for a long time but she has her job to do, as did recently Bob Rae, Nycole Turmel, and John Lynch-Staunton (whoever he is).

Leaving aside historical footnotes, when you look at leadership conventions, not only is BC’s winning percentage quite miserable, the lack of participation by BC candidates also stands out, at least in Liberal and Conservative races. With the NDP, British Columbians keep running … and keep losing.

The Liberals

The BC story is not very compelling when it comes to the Liberal Party of Canada leadership races. Again, I’m counting John Turner and he accounts for 67% of all BC candidates in the past 148 years. Joyce Murray is the other in 2013. That’s three candidates over 10 leadership races totalling 47 contestants. Well, it could be worse. Alberta Liberals haven’t found a way to show up at all. Neither has New Brunswick, PEI or Newfoundland, despite viable leadership candidates over the years like Frank McKenna, Brian Tobin, and Joe or Rob Ghiz.

Table 2: Candidates listed by province for each Liberal convention (winner in bold)

For a long time, the Liberals just didn’t have many conventions because their leaders were successful. MacKenzie King served for 29 years ! He fended off two Nova Scotians in 1919 and never looked back. Laurier lasted even longer – 32 years! Aside from the interregnum after Laurier’s death, Laurier and MacKenzie King spanned over 60 years between them. Incredible.

When WLMK finally retired in 1948, former Saskatchewan Premier Jimmy Gardiner sought the leadership losing to Louis St. Laurent. Gardiner remains the strongest western candidate (other than Turner) to seek the leadership of the Liberals.

The elected Liberal leadership has been a story of alternation between English Canada (principally Ontario) and Quebec. St. Laurent to Pearson to Trudeau to Turner to Chretien to Martin to Dion to Ignatieff to Trudeau. Very few Maritimers or Westerners. It’s the Upper-Lower Canada show.

In recent times, this reflects the woeful state of the Liberal Party in Western Canada from the mid 1970s to, basically, October 19th. While there have been regional heavyweights like Lloyd Axworthy, their ambitions were thwarted, in part, by a lack of regional caucus colleagues and party infrastructure. For many years, senators not MPs called the shot in western provinces for the Liberals. That is not a good starting point for a leadership race. John Turner, for all of his BC roots, drew heavily from his Bay Street and Montreal power bases.

Joyce Murray: representin’

Hedy Fry waved the flag in 2006, deciding to withdraw before the convention, choosing to endorse Bob Rae.

Joyce Murray finished second among six contenders in 2013, though Justin Trudeau walked away with over 80% support on the first ballot. In both Fry and Murray’s case, they were putting a stake in the ground for British Columbia which no one, but for Turner, had ever done in the party’s history.

The Conservatives

This analysis encompasses the Conservatives, the Progressive Conservatives, the Reform Party, and the Canadian Alliance. These are all parties that have governed or acted as the Official Opposition.

Table 3: Candidates listed by province for each conservative (all types) convention (winner in bold)

Of the 16 leadership conventions among Canada’s conservative parties since 1927, there have been eight BC-based candidates – a much stronger showing by British Columbians than in Liberal races. They make up 9 candidacies out of a pool of 75 contestants.

Howard Green: was said to walk the hallways with a Bible in one hand and a stiletto in the other

In 1942, two British Columbians challenged for the leadership, losing to incoming leader John Bracken from Manitoba. HH Stevens had been a major force in RB Bennett’s government prior to a bitter break whereupon he led his own party – the isolationist Reconstruction Party – in the 1935 election, surpassing the fledgling CCF and gaining 8.7% nationally. He split the vote in the process and decimated the Conservatives. He won only one seat – his own. Howard Green had a long career in Parliament ultimately serving as Minister of External Affairs under Rt. Hon. John Diefenbaker. Both Stevens and Green were from Vancouver.

E. Davie Fulton from Kamloops challenged for the leadership twice, in 1956 against Diefenbaker and again in 1967, when he sought to succeed Dief. He lost to Nova Scotian Robert Stanfield. Fulton would serve as Justice Minister but returned to BC in an ill-fated stint as provincial Conservative leader where he was trounced by WAC Bennett. In both conventions, he finished third and was probably BC’s best hope as prime minister material for decades.

Rt. Hon. John Diefenbaker and two-time leadership rival Hon. E. Davie Fulton

Fulton’s leadership runs deserve attention. He was a national figure who, as Justice Minister, had attracted the best and the brightest. A Catholic, and bilingual, he worked hard to develop support in Quebec. As Minister, he unsuccessfully proposed the Fulton-Favreau formula to bring about the patriation of the Constitution. In 1967, he had the support of future prime ministers Joe Clark and Brian Mulroney. He was seen as a modern man when he lost to Diefenbaker, and perhaps missed his window when he lost in 1967, though still only in his early 50s.

An interesting footnote from the 1967 PC convention was the candidacy of Mary Walker Sawka. Not much is written about her candidacy but it appears she was a filmmaker from Vancouver. Her candidacy was last-minute and she garnered two votes. The Globe & Mail cruelly reported that Walker Sawka “looked like a housewife who had mistakenly wandered on stage while looking for a bingo game”. She is the first BC woman to seek the leadership of a major political party.

An interesting footnote from the 1967 PC convention was the candidacy of Mary Walker Sawka. Not much is written about her candidacy but it appears she was a filmmaker from Vancouver. Her candidacy was last-minute and she garnered two votes. The Globe & Mail cruelly reported that Walker Sawka “looked like a housewife who had mistakenly wandered on stage while looking for a bingo game”. She is the first BC woman to seek the leadership of a major political party.

Moving on to the 1976 PC leadership convention, Vancouver South MP John Fraser was one of 11 candidates seeking to replace Robert Stanfield. Stanfield had three runs at prime minister, losing to Rt. Hon. Pierre Trudeau each time, once by a hair.

Fraser, at the time, was in his early 40s. He lasted two ballots, finishing eighth, and bringing his support to Joe Clark. Clark started that convention third with 12% of the votes on the first ballot and prevailed when he garnered down ballot support, leaping past Quebec frontrunners Claude Wagner and Brian Mulroney. Fraser went on to serve as the senior BC minister in both the Clark and Mulroney governments, prior to becoming Speaker of the House of Commons.

British Columbians sat out the 1983 leadership tilt. Many BC Red Tories stuck with Joe, while a lot of ‘young turks’ from BC supported Mulroney.

The BC branch was very united behind Kim Campbell in 1993. Campbell had resigned her provincial seat mid-term in 1988 to run federally. She had had enough of the Vander Zalm government and sought to replace Hon. Pat Carney. She won Vancouver Centre (back when PCs could win in the urban core) and was appointed Minister of Justice. She built a considerable profile and went on to serve as Minister of National Defence.

The Mulroney government was deeply unpopular in its second term. Following its 1988 re-election on the strength of Free Trade, it brought in the controversial GST (which no government will remove now) and paid a heavy political price. Layered on was the ongoing constitutional quagmire following the failure of Meech Lake in 1990. The 1992 national referendum to approve the Charlottetown Accord failed badly and sealed Mulroney’s fate.

Unfortunately for successors, he did not leave a lot of time for a leadership convention in advance of a general election. Five years were almost up. While there was some early hopes for Campbell following her convention win over Jean Charest, her support wilted over the summer and fall. She was annihilated by the Chretien Liberals, and with that, her leadership of the party ended.

For once, a BC born (Port Alberni) and raised politician had climbed to the top in a party’s leadership process. While the outcome was clearly a disappointment for her, Rt. Hon. Kim Campbell remains the exception in 148 years of Canadian politics not only as a BC prime minister, but also as the only female prime minister.

Two more British Columbians round out the slate of those seeking the leadership of conservative parties. Keith Martin from the Victoria-area sought the leadership of the Canadian Alliance in 2000, finishing back in the pack.

The other contender is a bit of a stretch. Stan Roberts sought the leadership of the Reform Party against Preston Manning in 1987. He didn’t make it to the ballot but he was instrumental in the formation of the Reform Party. I’m including him because he was an interesting character. A Liberal MLA in Manitoba. A head of the Canadian Chamber of Commerce. A VP of Simon Fraser University. A candidate for the BC Liberal leadership in 1984, losing to Art Lee. A federal Liberal candidate in Quebec in 1984 (unsuccessful). And finally a contestant for the Reform leadership. I will count him as a BCer for the purposes of this list. We need all the help we can get.

Of the 16 total conventions across the conservative movement, Albertans have won 44% of them. Rt. Hon. RB Bennett was first then a long wait until 1976 when Joe Clark won the PC leadership (and he would win it again in 1998). Stockwell Day, Preston Manning, Stockwell Day, and Stephen Harper round out the list. Alberta has had a strong run in modern times and possibly more to come. Having Albertan Rona Ambrose as Interim Leader seems to be rubbing it in!

Unlike the Liberals, conservatives prefer to go outside Ontario and Quebec, only choose four of 16 from Upper/Lower Canada and not an Ontarian since 1948.

The CCF / NDP

British Columbians have been a part of seven of eleven CCF/NDP conventions since 1932. The first two leaders – JS Wordsworth and MJ Coldwell – were elected unanimously. (Technical point: I’m counting leadership challenges to incumbent leaders in 1973 and 2001).

Table 4: Candidates listed by province for each CCF/NDP convention (winner in bold)

Frank Howard reels in 50 lb ling cod near Klemtu. He reeled in a lot of votes over the years too.

BC’s presence at CCF/NDP conventions starts with Frank Howard, a strong Trade Unionist who hailed from northwest BC and served as an MP for 17 years and, later, MLA from Skeena.

Howard’s story is a fascinating one and is recorded eloquently by Tom Hawthorn in Howard’s obituary. He was a fighter who rose from “Cell Block to Centre Block” – an ex-con from the humblest of roots who fought hard for his constituents. He would lose the leadership race in 1971 to David Lewis.

The 1975 NDP convention that elected Ed Broadbent was the scene of the strongest bid by a British Columbian to lead a major party, at that time. Rosemary Brown, then an NDP MLA from Vancouver, finished second with 41% on the final ballot. The first Black politician to seek the leadership of a major party, Brown received many accolades after she retired from elected politics in 1986, including an Order of Canada and Order of BC. She was also featured on a Canada Post stamp.

The 1975 NDP convention that elected Ed Broadbent was the scene of the strongest bid by a British Columbian to lead a major party, at that time. Rosemary Brown, then an NDP MLA from Vancouver, finished second with 41% on the final ballot. The first Black politician to seek the leadership of a major party, Brown received many accolades after she retired from elected politics in 1986, including an Order of Canada and Order of BC. She was also featured on a Canada Post stamp.

Ed Broadbent had a long run as leader, but when he left, British Columbians jumped in. The 1989 convention saw three west coasters jump in: former BC Premier Dave Barrett, MP Ian Waddell, and grassroots member Roger Lagasse. Barrett is the only BC premier to ever seek the leadership of a federal party.

A great read on Dave Barrett’s government, by Geoff Meggs and Rod Mickleburgh

Barrett was a strong contender, but lost to Yukoner Audrey McLaughlin. McLaughlin had been elected in a by-election to replace “velcro lips” and had a different style than Barrett, setting up a classic showdown. Of 2400 votes cast, only 80 separated the two on the first ballot and even fewer after the second ballot (Waddell and Lagasse dropped after the first ballot). This convention had some candidates, including MP Simon de Jong, wearing an invisible mic. To the consternation of many participants, CBC TV revealed the inner workings including backroom negotiations between de Jong and Barrett. de Jong was heard to say, “Mommy, what should I do?” He went to McLaughlin, who defeated Barrett 55% to 45% on the final ballot. Another close call for a BC candidate.

Svend got a lot of media in his day

McLaughlin tanked in the 1993 convention, hampered by unpopular NDP governments in BC and Ontario. Of the two remaining NDP MPs in BC, one was the brilliant yet polarizing Svend Robinson. Svend – any observer in BC would know who you were talking about – was at the forefront of major issues concerning the environment, aboriginal rights, and right-to-die. He also had a reputation as an excellent constituency MP. In 1995, he was 43 years old but had already served 16 years in Parliament. Herschel Hardin from Vancouver was also a candidate in the process.

The 1995 convention had an incredible outcome. For the first time in NDP history, a British Columbian led after the first ballot. Svend had 38% to Alexa McDonough’s 33% and Lorne Nystrom’s 32% (Hardin was part of the process but didn’t make it to the first ballot).

Svend sized up the result and decided that there was no way he could win. In an unprecedented move, he withdrew from the race – despite leading – handing the leadership to McDonough. And so went another BC leadership candidate.

The 2003 NDP convention that elected Jack Layton did not see a significant BC presence, with only grassroots member Bev Meslo offering her name.

Nathan Cullen: Next up?

In 2012, MP Nathan Cullen emerged as a contender through the course of the campaign, taking on favourites Tom Mulcair and past-party president Brian Topp. Cullen rose from 16% to 20% to 25% on consecutive ballots but that’s where it ended. He couldn’t make it past Brian Topp to get to the showcase showdown.

BC’s immediate future in leadership races

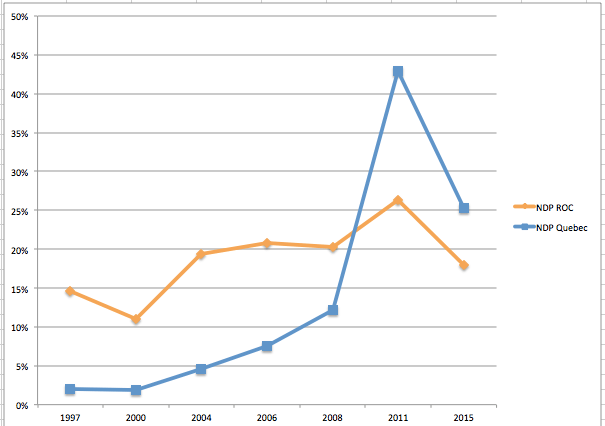

As NDPers ponder their fate and their future, they may well grant Tom Mulcair another chance. He delivered more seats than any other leader except Layton, but clearly fell far short of expectations. If he does move on, BC may well be in the heart of another national leadership race with Nathan Cullen surely a leading contender. MPs from BC make up almost a third of the NDP caucus which puts a BC candidate in a good position.

The Conservatives also face a choice. Once again, Alberta is in a strong position having elected 29 of their 99 MPs, while BC’s Conservative caucus slipped to 10. Albertans Jason Kenney and Michelle Rempel are two candidates that spring to mind as contenders, along with Ontario’s Kellie Leitch and Tony Clement, Quebec’s Maxime Bernier, and Nova Scotia’s Peter Mackay. Saskatchewan Premier Brad Wall ruled himself out.

But what about a BC candidate? My view is that it would be good for Conservatives in BC to have an oar in the water in this race, if for nothing else but to show up.

If this lengthy analysis shows anything, British Columbians are less likely to show up to a Liberal or Conservative race, and when they do, the results speak for themselves. While the Conservatives have been more active than Liberals, as the third largest province, there should be someone in that race. And the next NDP race. And when Justin retires in 2035 (because it’s 2035), there should be a British Columbian in that race too.

Ed Fast – you led the TPP negotiations. What say you? Dianne Watts – you led the fastest growing city in Canada – a strong urban, female voice – what your party needs. Cathy McLeod – a former small town mayor who was re-elected in a tough seat. Alice Wong – putting a Chinese candidate on the national ballot, and, frankly, a constituency where the Conservatives have a strategic advantage. James Moore – c’mon, you wanna work at a law firm and miss this? Now firmly ensconced as a British Columbian, Stockwell Day would be a major contender if he stepped up, but Stock would likely say that the Party needs renewal. A business case can be made for many BC Conservatives to show up on the ballot, for BC’s sake, not to mention their own electoral hopes here.

In conclusion, BC is a tough place to represent in Ottawa. The travel imposes a heavy toll on individuals let alone their families. Serious kudos are deserved for anyone who strives to lead from British Columbia. My hat goes off to those who have tried whether they were serious bids or quixotic ones. Combing through history to write this piece, I am struck by the quality of candidates from BC who didn’t make it.

The ambivalence of British Columbians to federal politics may in fact be the greatest handicap to success.

When 148 years are counted up, among born and raised British Columbians, only Kim Campbell can truly say that she made it to the mountaintop, as brief as it was. Hopefully we’ll see more try.

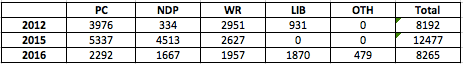

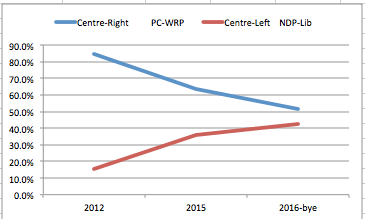

Compared to the turnout in the preceding general election, both Coquitlam-Burke Mountain and Vancouver Mount Pleasant had the lowest turnouts of any BC by-election since 2004.

Compared to the turnout in the preceding general election, both Coquitlam-Burke Mountain and Vancouver Mount Pleasant had the lowest turnouts of any BC by-election since 2004.

An interesting footnote from the 1967 PC convention was the candidacy of

An interesting footnote from the 1967 PC convention was the candidacy of

The 1975 NDP convention that elected Ed Broadbent was the scene of the strongest bid by a British Columbian to lead a major party, at that time.

The 1975 NDP convention that elected Ed Broadbent was the scene of the strongest bid by a British Columbian to lead a major party, at that time.